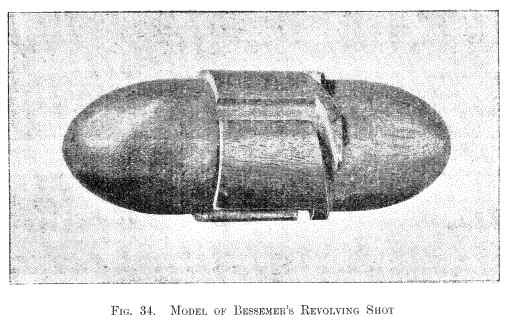

officers, who were going to the Crimea. Among the guests present on that occasion was Prince Napoleon, to whom I was introduced by my host as the inventor of a new system of firing elongated projectiles from smooth-bore guns. I happened to have with me a tiny pocket model, made in mahogany, of one of these new projectiles, which, in order that it might be more easily understood, had the passages for the escape of gas formed in its exterior surface, instead of in the interior, as will be seen from the annexed engraving, Fig. 34, representing in full size this little model projectile, which I made more than forty years ago, and which is still in my possession.

Its action was very prettily shown in this way: an upright glass tube of 1 3/4 in. internal diameter (accurately fitting the shot) had its lower end stopped up so that it resembled the barrel of a gun. If the model shot were put into the upper end of this glass tube, when held in a vertical position, it could not sink down to the bottom without displacing the air contained in the tube. This air necessarily found an escape through the external passages; and by the force induced by the escape of air in the direction of a tangent to the circumference, a slow and steady rotation of the little mahogany projectile was observed, as it gradually sank down to the lower end of the glass tube. Prince Napoleon was very much pleased with the idea, and said that he was sure that his cousin, the Emperor, would take great interest in my invention, and that he would get an appointment for me to show it to him. A few days later, I received a note from Colonel Belleville requesting my attendance on the following morning at the Tuileries, where I had a most interesting interview with the Emperor, who gave me carte blanche to go to Vincennes, and there order to be made everything that was necessary to fairly test my invention. I, however, found that it was much more difficult to get what I wanted made at Vincennes than it would have been at my own works in London, where other matters required my attention. I consequently sought another interview with the Emperor, when I explained this fact to him, and asked permission to make the projectiles in London, and bring them over. No objection was raised to this proposal, and as I was about to take my leave the Emperor said: "In this case you will be put to some expense; I will have that seen to."

A few days after my return to London, I received a letter from the Due de Bassano, enclosing an autograph letter from the Emperor, addressed to Messrs. Baring Bros., Bankers, London, giving me credit for "costs of manufacturing projectiles," but without naming any sum. Whatever private instructions there may have been given as a limit to the amount of credit, none were visible to me; and I could not help forcibly contrasting this delicate and generous treatment by the Emperor with the curt refusal of our own military authorities to give my invention a trial at home.

In a few weeks, the projectiles necessary for the experiments were all made under my own eye, and packed ready for transport. There were 24-lb. and 30-lb. elongated shots of 4.75 in. in diameter, fitting the 12-pounder smooth-bore French guns, gauges for which had been sent to me in order to ensure accuracy in size. I had been provided with a special permit to pass the Customs House at Calais, notwithstanding which, my passport was rigidly examined, and I was looked at and questioned by all sorts of officials before I was allowed to proceed on my journey.

I, as specially directed, went straight on to Vincennes on the following morning, and was met by Commandant Minié (the inventor of the rifle which bears that name), who had received instructions to superintend the experiments and report thereon to the Emperor.

In the large open plain known as the Polygon, at Vincennes, a series of thin wooden targets had been set up, one behind the other at about 100 metres apart. My projectiles were fired point-blank at these targets, and generally passed through five or six of them before reaching the ground, making round holes in each, and showing that all the shots went end-on. In order to enable us to measure the amount of rotation of the shots, I had given them a thin hard coating of black Japan varnish, which was partly scratched off and scored in lines when passing through the thin planks. There were a few inches of snow on the ground at the time these experiments were made, and we could observe the projectiles ricocheting away to the left as a result of their continued rotation after striking the ground, and sending up the snow in little jets, thus indicating where they were to be found. On recovery, the spiral lines scored on the japanned surface in its passage through the target gave every facility for ascertaining the angle,

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |