process; nor did the extreme jealousy of the steel trade prevent such unfavourable reports from being published with all the usual embellishments naturally arising from ignorance or prejudice.

This adoption of my process by the ironmaster for making rails went far to discredit it. If you told a steel maker that it was being largely used, he would say: "Well, perhaps it is good enough for rails; anything is good enough for rails." Indeed, it is true that in the case of rails moderate variations of temper were not fatal. The rail might be a little too hard or too soft, but in either case it was immensely superior to iron, and so it passed muster. But it was when boiler plates, ships' plates or crank-axles, were required, that the inexperienced ironmaster, with his inexperienced workmen, began to realise the fact that steel was wanted of a certain standard of quality for special purposes; and that he must train his men, who were little else than mere apprentices learning a new trade, to produce these several qualities with certainty. It is not at all surprising, under such conditions, that Bessemer steel acquired the character of being uncertain and not trustworthy. Hundreds of workmen who had never before worked a plate of steel in their lives, and were totally ignorant of its proper treatment, were engaged in the manufacture of steel boilers and in building steel ships. Such workmen had no hesitation in putting a hot steel plate down on the floor, with one end in a puddle of water; or in placing a mass of cold iron on a red-hot plate to keep it flat while cooling; or, on the other hand, in overheating it in a furnace, quite unconscious that no steel would bear the same high temperature as iron. And when they had thus succeeded in spoiling a plate originally of good quality, they did not hesitate to lay all the blame on the Bessemer process, which they honestly believed was the sole cause of the mischief that their own want of experience as steel-smiths had occasioned.

When the investigation of the character and properties of Bessemer Steel, undertaken by Colonel Eardley Wilmot at Woolwich Arsenal, was completed, all the early difficulties of the process had been entirely removed. We had become intimately acquainted by use, and by analysis, with several brands of Swedish pig-iron, from which either soft ductile iron, or steel of any degree of carburation, could be -- and in fact was -- daily produced at our Sheffield works, on a commercial scale without the employment of spiegeleisen. We had command also of a practically unlimited supply of a very high-class non-phosphoric hematite Bessemer pig-iron, suitable for conversion into steel. We had also magnesian pig-iron from Germany, and Franklinite pig-iron from the United States, the latter containing about 11 per cent. of manganese, which was greatly preferred for deoxydising steel derived from British coke-made iron. We had our converting vessels at that time mounted on axes; and, infact, the Bessemer process was so complete, and so under command, as to enable us to produce at will, pure Swedish steel of all tempers down to soft iron, and also mild hematite steel, as good in all respects as we are able to make at the present day. Above all, we had the advantage of the knowledge and experience of Mr. W.D. Allen, Managing Partner of the Bessemer Steel Works at Sheffield. In proof of my assertion that the Bessemer process was at that time as perfect in results as at any later date, I will give a few examples of our products, commencing at a period several months prior to the advent of Sir William Armstrong at Woolwich, covering the whole five years of his official power, and extending for some years after his departure from the Arsenal.

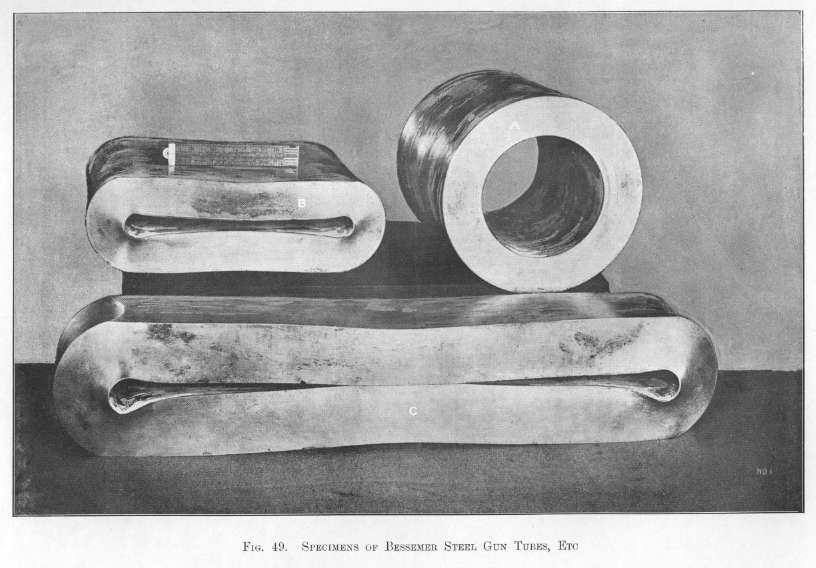

Fig. 49, Plate XIX., is a photographic reproduction of some test specimens, to which I have already alluded, representing three out of four pieces of gun-tube tested at Woolwich, two of them made of mild steel, and the others being nearly chemically pure iron. It will be remembered that these cylinders were made at my works at Sheffield, and were crushed flat, in the presence of Colonel Wilmot and myself at Woolwich, while cold, under the heavy blows of a large steam hammer. In order to give a correct idea of the nature and appearance of these crushed gun-tubes and hoops, I refer my readers to the photographic reproduction, Fig. 49. The specimens illustrated were made of Bessemer hematite pig- iron, converted into steel by the Bessemer process, and of a quality precisely the same as we were, at that early period, daily using in the manufacture of railway-carriage axles, piston-rods of steam engines, and other general machine forgings.

In the illustration, A represents a portion of a gun-tube for a rifled gun, machined and finished; B is one of these pieces, flattened, as shown, and C is a larger hoop, crushed flat with the heavy blows of the steam hammer. The two sides where the bend takes place are immensely stretched on the exterior

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |