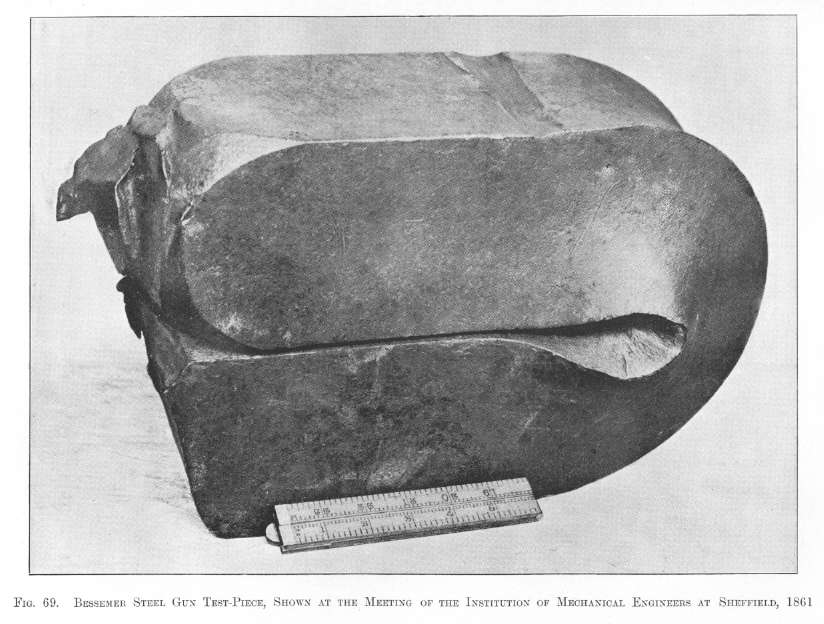

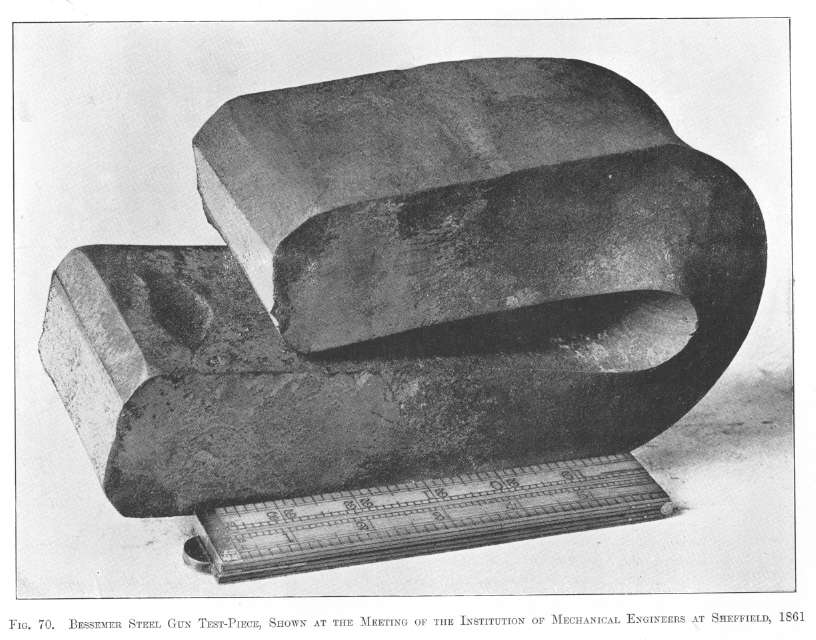

The 18-pounder gun exhibited on the occasion of Sir William Armstrong's visit to Sheffield sufficed to show that in the short period of eight hours a gun-bock of forged steel could be obtained from pig-iron. The gun-ends bent cold, which were placed on the table to illustrate my paper, bore testimony to the quality and toughness of the steel of which this gun, and many others, had been made. Some of these I have already dealt with, and I have selected for illustration, in Figs. 69 and 70, Plates XXVIII and XXIX, two more striking specimens from among the number I displayed.

Month after month rolled on, and no application came from Woolwich for any of the Bessemer steel, which Sir William Armstrong admitted he had never tried for guns. Nevertheless, we continued making guns to go abroad.

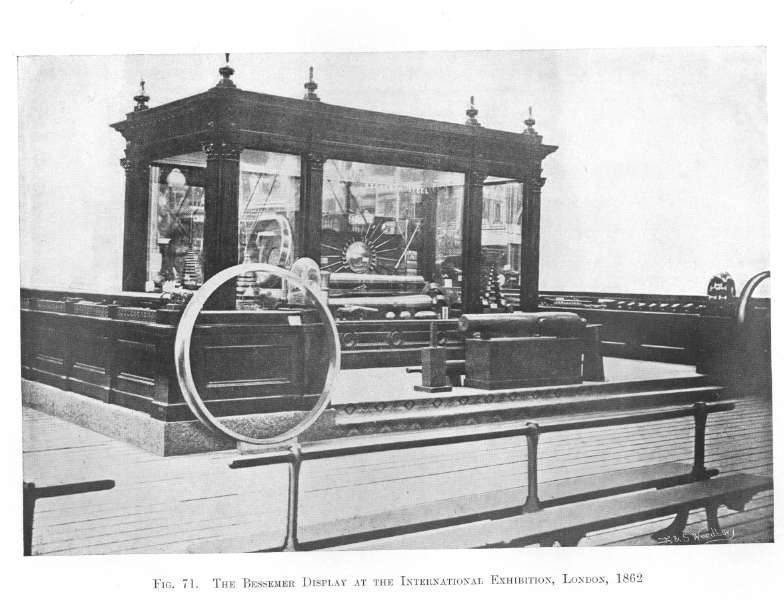

The managers of the International Exhibition of 1862, fully appreciating the importance of this new steel process, allotted me a very large space, measuring no less than 35 ft. by 35 ft., equal to 1225 square feet area, with a free passage 8 ft. wide all round it. A photographic reproduction of my exhibit is given in Fig. 71, Plate XXX; it was taken from an imperfect print made in the dark days near the close of the Exhibition.

It will be seen, however, that on a pedestal in front of the central case is a rough forging of a 24-pounder gun with trunnions formed out of the solid; inside the case is a finished 18-pounder gun, a large and massive gun-hoop, etc., etc. There were also shown an embossed steel shield, a star formed of bayonets, a group of revolvers, cavalry swords and sheaths, military rifles, projectiles, a model breech-loader, etc. On the external counter was placed a 4-inch diameter bright steel shaft, 35 ft. long, in one piece, steel hydraulic press cylinders, railway axles and carriage and engine tyres, a circular saw, 7 ft. in diameter, every size of steel wire for ropes, steel bars and rods of all sizes, and, in fact, an immense number of other interesting objects that would fill a long catalogue.

The enumeration of these objects may seem commonplace enough at the present day, but at that time they were undoubtedly marvellous industrial results, and an immense excitement was caused by this display of the new steel, which attracted engineers, ironmasters, and steel manufacturers from every part of Europe and America. Indeed, I exhibited beautiful specimens of steel made, under my patents, both in France and in Sweden.

I cannot refrain from comparing the small effect which my exhibit made upon the stolid inertness and indifference of the War Office, with the results it produced on the active mind and business instincts of one of the most important and most intelligent Lancashire engineers, an employer of some 5000 workmen. I refer to the late John Platt, M.P. for Oldham, where his large works were situated. This successful engineer visited the Exhibition on the opening day, and at once grasped the importance of my steel process from an engineering point of view; he pointed out its value to some of the heads of departments in his own works, who made the same high estimate. Mr. Platt, on the fourth or fifth day after the opening of the Exhibition, had a long interview with me, and said that he himself, and nine of his immediate friends and connections, wished to join in the purchase of one-fourth share of my patent. It was very natural that I should entertain an offer to recoup me for my large expenditure, and at the same time to afford a handsome profit, thus avoiding some of the risks to which all patent property is subject. But I had so strong a faith in the great future of my invention -- a faith based on proved facts -- that I felt bound to decline his offer, as I desired myself and my friend and partner, Robert Longsdon, to retain the absolute control of the patents, and thus be able at any time to raise or lower my royalties as I thought best. Mr. Platt, however, approached me again on the subject a few days later, saying that he and his friends were prepared to waive all right to control the patents so long as I retained one half, trusting that in the interests of that half I should do what was best for myself, and consequently what was best for them. This proposal quite met with my approval, in principle; that is, I was willing to enter into a bond with these gentlemen to hand over to them five shillings out of every pound paid to me by way of royalty by my licensees, the patents, price of royalties, etc., being governed by myself and my partner, Longsdon, just as though no such bond were in existence.

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |