It will be seen from the foregoing that I had formed a pretty accurate estimate of the inertness and inactivity of the British Admiralty, when I decided on not wasting my time in endeavouring to awaken them to a sense of the vast national importance of employing mild cast steel for shipbuilding.

Private shipbuilders and shipowners had, as I felt assured they would, availed themselves largely of the many advantages possessed by this material, and had set an example of alertness and activity to the officials of the Admiralty, an example which they wholly disregarded. Thus, year after year rolled by, and still there were no signs of the Admiralty waking up to the consciousness of the great metallurgical revolution that was rapidly spreading over Great Britain and the whole continent of Europe, and that had already extended in full force to the energetic people of the United States. In fact, everywhere steel was replacing iron for innumerable structural purposes, varying from viaducts and bridges of large span, down to such small items of domestic hardware as milk-cans and saucepans.

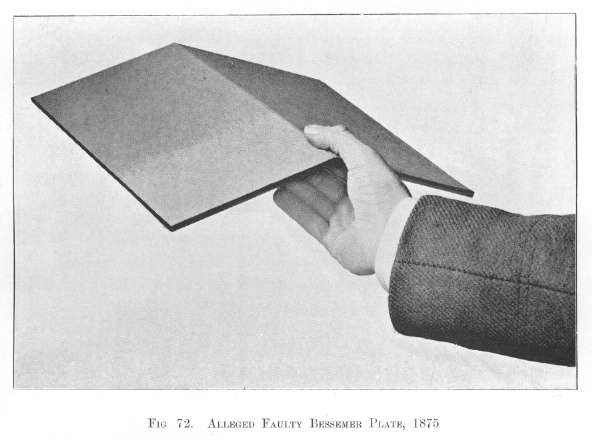

After ten years of indifference on the part of the Admiralty, it was discovered that, notwithstanding the fact that the Bessemer process was a British invention, the more active and more enterprising officials of the French Admiralty had fully recognised the value of steel for the construction of ships of war, and that the French Government were far advanced with the large iron-clad, "Redoubtable," then being built of steel at L'Orient, and that they were also pushing forward two other large steel vessels of war, the "Tempete" and the "Tonnerre," which were then being built of steel in French ports. When this important fact came upon our quietly-sleeping Admiralty officials, then, and not until then, did they rub their eyes, and wake up sufficiently to recognise their position. They knew that this important fact could not long be concealed from the public press, and would thus come to the ears of John Bull, who is apt to demand a scapegoat when he finds that his country has allowed itself to be beaten in the race with other nations. Possibly it was felt by the Admiralty that some reason or other ought to be advanced for their not having commenced to build a single steel war ship, while our nearest neighbour had nearly completed three magnificent steel ironclads. Whether this surmise be accurate or not, it is certain that, with the consent of the Admiralty, Sir Nathaniel Barnaby, then the Chief Naval Architect of the Royal Navy, read, in 1875, a paper on "Iron and Steel for Shipbuilding," before the Institution of Naval Architects, in which paper the alleged "uncertainties and treacheries of Bessemer steel in the form of ship and boiler plates" were explained to the public. This comprehensive summing up of the uncertain quality and undesirable characteristics of the material was still further emphasised by Sir Nathaniel Barnaby holding up to the meeting an isolated example of the failure of a thin piece of plate metal, said to be a part of a Bessemer steel ship-plate, which had cracked when it was bent to a very small angle.

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |